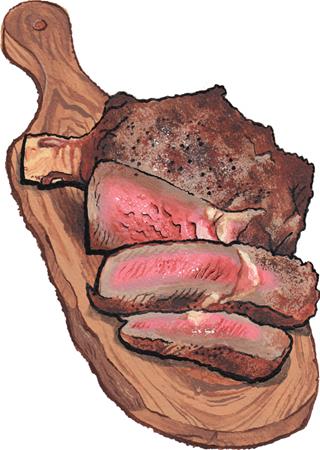

Not long ago, we did a taste test. Two nearly identical steaks: both fat ribeyes, both from Carman Ranch in Oregon so the cows had similar genetics, had eaten the same diet, and been raised to the same standards and in the same conditions. Both cooked to a nice medium rare. The only difference: one of the steaks was dry aged and the other one was not. The difference in flavor was unbelievable. The steak that hadn’t been dry aged was good, but the dry aged steak was far more tender and the flavor was much richer, more nuanced, and lasted much, much longer. It was no contest.

What is dry aging anyway?

After an animal is slaughtered, the carcass is chilled down and broken apart into big sections called primals. At this point the meat must rest. After an animal dies its body goes into rigor mortis and the muscles stiffen. If you tried to cook up the meat right away it would be very tough and chewy. Resting makes the meat more tender. It can be done two ways: “wet” or “dry.” The vast majority of meat is wet aged: the primals are vacuum sealed in plastic and then allowed to rest in refrigeration. It’s called wet aging because the meat is basically marinating in its own juices inside the plastic. With dry aging, the primals are left uncovered in carefully controlled conditions with cool temperatures and high humidity.

During dry aging, the meat dries out and loses weight as a bit of the moisture evaporates. The edges of the meat become so dry that they need to be trimmed off when the primal is broken down into individual cuts of meat, decreasing the weight even further. Since meat is sold by weight, lower weight equals lower profits. It’s exactly the same logic as cheesemakers use when they seal blocks of cheese in cryovac. But what sealing adds in profit it subtracts in flavor. As cheeses mature they release gas, which gets locked in cryovac and creates off flavors. Being left open to the air lets the cheese breathe, which allows more complex, longer lasting flavors to develop. The same thing happens with meat: if you age it in plastic, it can develop more sour, bloody flavors (that sounds bad, but practically all the meat we buy these days is wet aged, so we’re accustomed to it). Dry aging, on the other hand, lets the meat breathe and release off flavors that develop.

Until about 30 years ago, all fresh meat was dry aged. But then the meat industry figured out that if you put the meat in a plastic bag, not only did it lose less moisture weight, but you could also finish the aging process faster. Way faster. Meat can be wet aged in just a few days. Dry aging, on the other hand, usually takes at least a couple of weeks. It costs more to hold onto the meat for longer, so if your goal is to make a quick buck you’re better off with wet aging.

That extra time spent dry aging makes a huge difference for flavor.

More time spent aging means that the enzymes in the meat have more time to create all sorts of deeper, more complex flavors. It’s the same thing that happens when you let bread dough proof and ferment longer before you bake it, or when you let pasta take longer to dry: the extra time results in richer flavors. The water evaporation that happens during dry aging is important, too. Less water in the meat concentrates the flavor, making it more intense.

Why is dry aged meat so hard to find?

It’s more expensive. It’s time consuming. It requires special temperature- and humidity-controlled facilities that not all butchers or meat processors have. It also takes craft expertise to oversee the process and make sure that the meat is aging properly.

Even butchers that do dry aging don’t dry age all of their meats. Dry aging isn’t beneficial to all cuts. In general, the best candidates for dry aging have plenty of fat and bone around the meat. Cuts that are too lean or too small dry out more quickly. That’s a big part of why beef is the meat we’re most likely to see dry aged: since beef primals are bigger than, say, pork primals, they stand up to aging better.

All that being said, if a butcher is going to the trouble and expense to dry age their meat and you can find it, it’s likely to be a treat. You’ll usually be told how long the meat was dry aged, and that’s important. Two weeks is enough to develop significant flavor. More than that and the flavor continues to develop, getting more intense and often a bit funky. Some people love that, others find it off-putting. The ribeyes we have from Carman Ranch get two weeks of dry aging, which is plenty to create huge, sweet, intensely beefy flavor.