A few days ago, I tried an experiment: I cooked up two batches of penne side by side. One was made by Barilla, the largest pasta maker in the world. The other was made by Martelli, a tiny Tuscan pasta producer we’ve been working with for years. Though they look almost identical and are made within 100 miles of one another from essentially the same ingredients, the results were remarkably different.

Before I get to the flavor, a bit of back story.

Barilla and Martelli both started as family operations. Pietro Barilla opened a small bakery and pasta maker in Parma, Italy in 1877. (While we don’t tend to think of selling bread and pasta in the same shop in the US, in Italy it’s very common to find bags of pasta sold at bakeries to this day—a remnant of the tradition of one person in the village making all the flour-based products.) Likewise, the Martelli facility in Lari, Italy, has been a pasta factory since the 1870s. Martelli brothers Dino and Mario took over the operations in 1926, after having worked there for many years.

If you walked into either Barilla or Martelli a century ago they probably looked pretty similar. Pasta has been made commercially in Italy since the 1400s, when it took the strength of two men (or one horse) to force pasta dough through molds (called “dies” in the pasta biz). By the 1600s the first mechanical pasta makers appeared on the market, and by the late 1800s copper and bronze dies were widely used to shape pasta. “Factories” like Barilla’s and Martelli’s, powered by the new steam and coal engines of the machine age, popped up all over Italy.

Fast forward a hundred years.

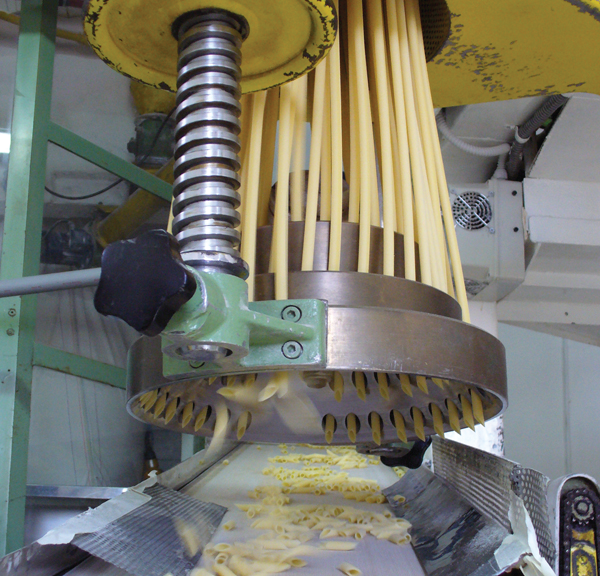

When I visited Martelli recently, outside of a digital thermostat in the drying rooms and the clear presence of electricity, I could have easily mistaken the place for a pasta maker circa 1870. They still mix the dough in open machines and extrude it through copper dies, then lay it out to dry slowly. Meanwhile, there’s this video about Barilla’s factory that shows they’ve clearly come a long way, baby. Or have they?

It turns out pasta innovation, while good for scale and a business’s bottom line, is not always very good for flavor.

First, about those bronze dies.

Martelli still uses bronze dies to shape their pasta. The imperfect metal gives pasta a much rougher texture which grips the sauce and doesn’t leave it in a puddle on the plate. Touch a piece of Martelli pasta and it feels like sandpaper. Barilla pasta, on the other hand, feels like glass. Barilla uses dies coated in Teflon, which has been the industry standard since the 1960s. I couldn’t swear to why Barilla made the switch, but I bet, like most business decisions, it was due to cost. Bronze dies are much more expensive, and require more frequent maintenance than dies coated with Teflon. Teflon dies also allow for faster pasta production, since the dough slips through more easily. Pasta extruded through Teflon-coated dies has a smooth, nearly slick surface.

Pasta is more like bread than you think.

Bread dough that is allowed to proof and ferment longer has more flavor than bread produced more quickly. Same goes for pasta. Pasta that takes longer to dry develops a much richer, deeper flavor. To put it simply: pasta made without long drying time tastes like flour; pasta made with a long drying time tastes more like bread. Barilla’s pastas dry in as little as four hours. By contrast, it takes about fifty hours to dry a batch of Martelli.

I don’t mean to pick on Barilla. They share the same process as nearly any large-scale pasta maker, from Prince to the pseudo-artisanal De Cecco, all of whom have made cost-cutting decisions that cut into the flavor. It’s now to the point that most folks think of pasta as a vehicle for a sauce’s flavor, not something flavorful in and of itself. That is, until they try Martelli.

Back to the two bowls of pasta. How did they taste?

Side by side in the bowls, the two pennes were easily distinguishable: Barilla is ridged (“rigate” in Italian) and more yellow; Martelli is unridged and paler. Despite the lack of ridges, Martelli did a much better job of gripping the il Mongetto tomato sauce I dressed the pasta with; the Barilla felt slippery in my mouth and the sauce slid right off it in the bowl. The Barilla has a mild wheat flavor that was easily hidden beneath a sauce; Martelli has a deep, nutty, bready flavor that lingers long after I finished my last bite. Martelli tastes so good that I wanted to —and did—eat it plain.

Martelli only makes four—make that five—shapes of pasta.

Talk about a lack of innovation. While Barilla makes more than 120 shapes of pasta, for over a hundred years the Martelli family has made only four shapes: spaghetti, spaghettini, penne and maccheroni. Then last year they added a fifth, fusilli (a “modern” shape that was only invented sixty-some years ago). At this rate we may not see another shape sill the 22nd Century. Personally, I find their lack of dynamism refreshing. It certainly tastes good. And I’m not the only one who thinks so—Corby Kummer wrote in The Atlantic that “everyone should eat Martelli pasta at least once to know how great dried pasta should taste.”