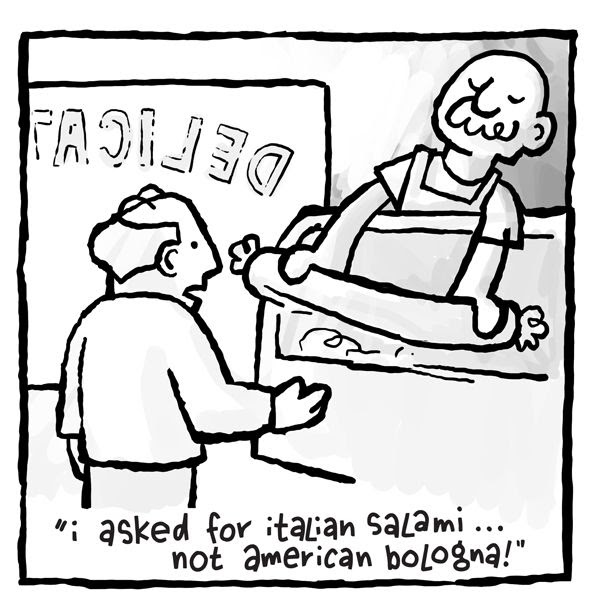

It’s been a dirty little secret for decades. The Italian salamis all of us merchants sell aren’t Italian. Also, the Spanish ones aren’t Spanish. The French ones aren’t French. In fact, none of them are what they seem. That’s because, with a handful of exceptions, foreign salamis are not allowed in the United States. We haven’t been trying to keep this from you, it’s just that no one has been discussing the issues around salami immigration in America.

This isn’t a political thing. It’s not caused by a caucus of Senators who are anti-salami and want all cured pork turned away at the border. It’s simply the byproduct of some well-intentioned regulation. Upton Sinclair’s book The Jungle kicked off a wave of much-needed meat industry improvements that continue to impact us today. One of the changes had to do with requiring federal meat inspectors to regularly inspect plants. That’s not too much of a problem for most American meatmakers since they’re usually a short drive away from an FDA office. It’s a real pain, though, when you’re making Toscano salami in a small village in Italy. The upshot has been that almost no foreign cured meat makers have been certified to sell to America. Those that have are big companies and they make a less interesting salami anyway.

What’s an American salami-hunter to do?

First off, don’t try to smuggle a suitcase of salami home from Europe. It’s illegal and they have security dogs at the airport and apparently dogs of all nations totally love salami. I know this from experience. Your best bet is to eat your fill while traveling then hunt for good salami at home.

The good news is hunting has never been easier at home. The last five years have provided us with — while not quite an explosion — a bona fide expansion of great cured American meat.

Some of it is very local, it never leaves its home county, so by all means check out the cured meat cases of delis when you travel. Good cheese shops can be helpful — cheesemongers are a curious sort and know a lot about who’s making food in their area. Micro breweries, too.

There’s also mail order. We carry salamis from a few of America’s best, including La Quercia in Iowa, Creminelli in Utah, and Columbus in San Francisco.

Look for salami sources that either cull their collection to a handful of items or sell a lot of volume—or both.

Salami, in spite of being cured, has a relatively short window of when it’s at its best so a slow-moving meat counter is an enemy of flavor. Sold young it’s too moist, the texture chewy and stringy, the flavors disparate and not blended. Past its peak it’s dried out, hard to gnaw on and very salty. When buying salami look for a pinkish hue and the sweet aroma of pork—it shouldn’t be dominated by spices. A soft, downy coat of mold is a good sign, too. It usually means its enjoyed its environment and is still moist and flavorful. If the mold is completely gone it could be a sign that the salami is over the hill, past its prime. You don’t have to eat the mold but it won’t hurt you either.