I grew up thinking there were four kinds of cheddar: mild, medium, sharp, and extra sharp. Oh yeah, and a fancy fifth kind: white. Though I didn’t know it at the time, those cheeses are all products of essentially the same methods: milk from dozens or hundreds of sources all trucked to the cheese factory, pooled together, pasteurized, and turned into enormous blocks of cheese. They were vacuum sealed in plastic and placed into refrigeration to age for a few months. The degree of sharpness, the one way the customer could choose between them, was a product of how much acidity was in the finished cheese.

In the last fifteen years, though, a few pioneering cheesemakers began experimenting with aging cheese a different way. They wrapped the baby wheels of cheddar in cloth. Soon clothbound cheddars, like the Cabot Clothbound Cheddar aged at the Cellars at Jasper Hill, were the big new thing. Only really, they weren’t new at all.

Cheddar has been wrapped in cloth in Britain for centuries.

The English have made cheddar since at least 1170, when King Henry II purchased more than 10,000 pounds for his court. (His larders must have been mouse heaven!) I can’t say for certain whether that cheddar was aged in cloth, but we do know that English cheesemakers have been using cloth since at least the 1600s. When colonial cheesemakers arrived in New England, all of the first cheddars made in America were wrapped in cloth. Those new American cheddars required a few adaptations, though: whereas England’s mild weather made for good conditions for aging cheese, the hot summers of New England made the cheese age—and dry out—too quickly. To counteract the heat, Yankee cheesemakers started covering the cloth wrapping with a layer of lard—a technique that’s used today to make Cabot Clothbound Cheddar. The lard never touches the cheese itself, just the cloth. It helps to keep in the moisture so the cheese mature more evenly.

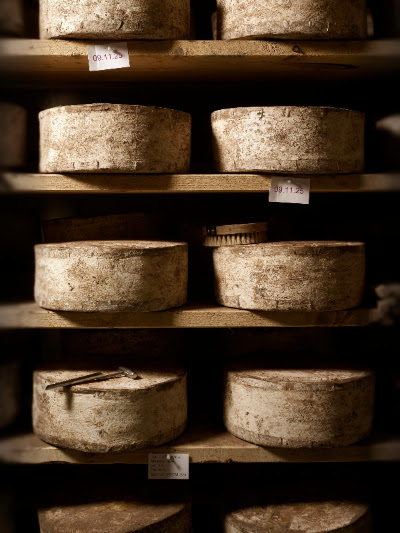

By the end of the 19th century, American entrepreneurs figured out how to wrap cheese in wax, which holds in moisture even better than lard. Wax—and later vacuum-sealed plastic, AKA cryovac—make cheesemaking easier. Not only does it keep in more moisture (which means more profit, since cheese is sold by weight), it also eliminates some of the labor of cheesemaking. While cheese wrapped in cloth needs to be flipped over regularly to mature evenly, a waxed cheese can be plopped in a fridge and left alone till its ready to sell. Cloth-wrapped cheese also needs to be brushed regularly to keep them clean. But the savings in weight and labor come at the expense of flavor. As cheese matures it releases gas, which gets locked in by wax and cryovac. That’s not good for flavor. Cloth allows the cheese to exhale, which lets more complex, interesting, longer lasting flavors not get overwhelmed.

One reason some people like wax and cryovac is that they let you age cheese for a lot longer. In the 1990s, extra old cheddars started showing up on the specialty market: two years, seven years, a decade, even. Ages like that are only with wax or cryovac’ed cheeses. If you try to age a clothbound cheddar for more than a couple of years it would completely dry out and the flavor would become way too salty. It’s like dog years compared to human years: clothbound cheddars age faster. Cabot Clothbound Cheddar reaches its peak at about 12 months old; that’s usually how old our wheels are.

While the clothbound aging technique was developed in England, that doesn’t mean it’s widespread there today. During World War II farmstead cheesemaking all but disappeared when the government required that milk be pooled together to make wartime cheese rations. After the war not many cheesemakers took up their old craft. Today there are only three or four traditional cheddars made in England.

Cabot Clothbound Cheddar tastes a bit different than English cheddar.

While English cheddars can be a bit vegetal and piquant, Cabot Clothbound Cheddar has a bit more caramelly, nutty sweetness. That sweetness is balanced with rich, brothy notes, some bright, fruity flavors, and that classic cheddar tang. Tying it all together is a bright acidity—what the Big Cheese Industry calls “sharpness.” (By the way, smaller cheesemakers usually avoid that word. If you want to impress a cheesemonger, next time you go to your local cheese shop ask for a nice “acidic” cheddar, not a sharp one.) The tangy-yet-sweet flavors make Cabot Clothbound Cheddar an eye-rollingly good companion for cider jelly. And sandwiches, burgers, or crackers—Cabot Clothbound Cheddar turns them all up to eleven.

When wheels of Cabot Clothbound Cheddar arrive to our cheesecave, they’re still wrapped in the cloth. By the time you get a piece at home, though, we’ve taken the cloth off so the whole piece is cheese. That means that the rind on your cheese is edible, if you want to eat it or toss it into a broth or risotto for extra flavoring. But before you pop it in your mouth or the soup pot, take a look at the rind—you may see an imprint of the cloth.