Today’s Calabria, the region at the toe of Italy’s boot, is one of the country’s poorest provinces. But once upon a time, 26 centuries ago, it was home to Sybaris, a town synonymous with wealth and excess. While Calabria may no longer have Sybaris’s fabled luxury, it does have at least one sybaritic indulgence: candied clementines dipped in chocolate.

Welcome to Sybaris, land of wealth and excess.

First, a bit of history. Founded around 710 BCE as a Greek colony, the settlement of Sybaris grew to phenomenal wealth and prosperity, even surpassing Athens in luxury. A busy port surrounded by fertile farmland, stories of Sybaris told by Greek and Roman historians paint a picture of opulence and self-indulgence. (At least, for some people. Much of the wealth of Sybaris was built by slaves.) Their lifestyle wasn’t only fun and games. They invented the first recorded chamber pot (quite the 7th century BCE luxury!). They created the first patent laws to protect the financial interests of cooks for their delicious recipes.

They had a good run, but within a few centuries Sybaris was gone. Greek historians paint a colorful picture of its demise. Around 510 BCE, a new leader called Telys exiled the town’s 500 wealthiest citizens and took all their money. The exiles traveled down the coast to the nearby settlement of Kroton. Telys demanded that Kroton force the exiles to leave. Pythagoras—who moved to Kroton in 530 BC and spent the next 35 years there living in a commune, theorizing about the hypotenuse, inventing musical tuning, describing the inaudible symphony dictating the movement of the planets, and preaching vegetarianism—urged local leaders to protect the exiles. Kroton’s leaders took Pythagoras’s advice. Sybaris declared war on Kroton. Kroton won, and the victors razed Sybaris. In fact, they razed it so thoroughly that it was lost for 2,500 years, until archaeologists finally discovered the ruins in the 1960s.

The Romans saw the city’s fall as divine retribution: the gods, displeased with the Sybarites’ excessive luxury, took their vengeance. That moralistic take remains in our modern English word sybarite, meaning a hedonist, a glutton, someone so interested in luxury and sensuality as to neglect everything else.

For all the Sybarites’ indulgences, citrus wasn’t one of them.

Citrons, the first citrus to arrive in the Mediterranean via traders from Persia, weren’t planted in Italy until the 3rd century CE, more than two hundred years after the fall of Sybaris. Had they known about citrus, though, you can bet the Sybarites would have grown them like crazy, since they’re a rare source of fresh sweetness in winter. Calabria’s climate is ideal, and today it’s the epicenter of Italian citrus. As Waverly Root describes it in his excellent, highly recommended book The Food of Italy, “Every citrus fruit you ever heard of is grown here [in Calabria], and probably one or two which you have not, like the megalolo and the verdello.”

Calabrian clementines are protected under an IGP. They’re a relative newcomer to the Calabrian citrus landscape—the first clementines anywhere date back to just 120 years ago. The first one was most likely a hybrid of a mandarin and a sweet orange, discovered in Algeria in the 1890s. Noted for its sweet, juicy flavor and thin, easy to peel rind, citrus enthusiasts soon carried clementines around the world. By the 1950s, farmers began planting clementine groves across Calabria, where the warm, sunny climate makes for a very long citrus season. The clementine harvest begins as early as mid-October and continues all the way into February. By contrast, the season for California clementines lasts only half as long. By January, those ubiquitous crates of Cuties or Halos in US groceries are packed with mandarins which, while also small and seedless, are botanically unrelated to clementines.

In the heart of the Calabrian plain of Sibari, the Rizzo family does the opposite of mono-crop agriculture.

About ten kilometers south from the heart of the ancient site of Sybaris, the Rizzo family does it all. They have rice paddies and olive groves. They have extensive vegetable gardens. They preserve their harvest in their own commercial kitchen, jarring everything they grow from itty bitty artichokes to homemade sauces. They keep a herd of 700 water buffalo and use the milk to produce a handful of farmstead cheeses. They grow everything from basil to goji berries in greenhouses powered by one of the largest arrays of solar panels in Europe. They power all of their operations using those solar panels and an on-site biogas converter. Most important for us, they also grow 55 hectares of clementines.

When ripe, their clementines are tiny, the size of a golf ball. The Rizzo family selects the very best fruits from the crop and candies them whole, peel and all. The clementines spend more than three weeks soaking in a sugar syrup bath (talk about sybaritic heritage!). When they’re ready, the peel is firm and toothsome and the flesh inside a sweet-tart pop of citrus flavor. When you bite into one, it bursts with syrupy juice that is what I imagine sunshine would taste like.

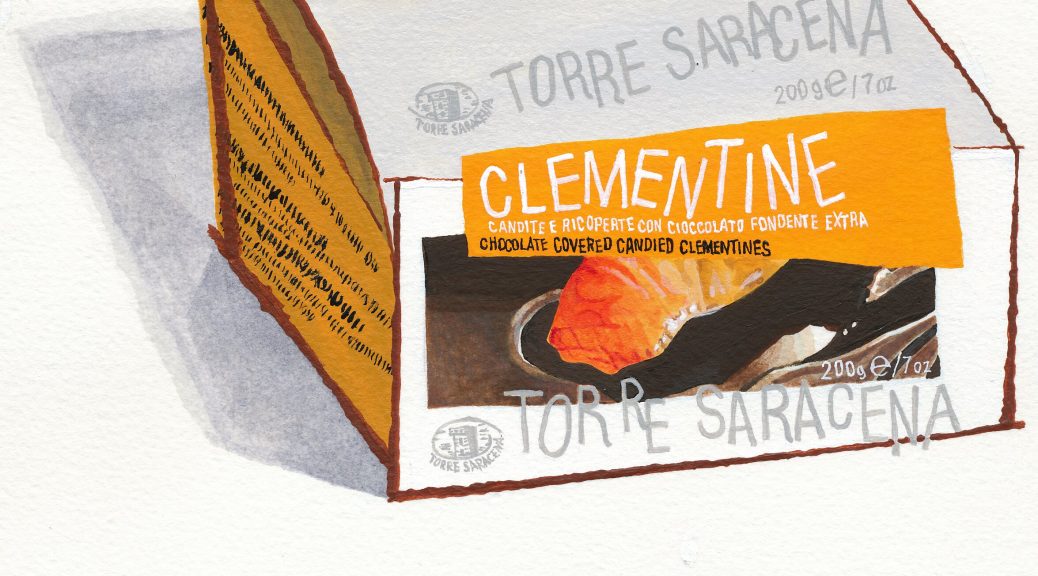

You could stop there—and the Rizzos do, offering jars of whole candied clementines, which are fabulous for garnishing cocktails, cakes, or just nibbling. But to truly get into the Sybaritic spirit, the Rizzos take the clementines, cut them in quarters, and enrobe them in dark chocolate. The result is dreamy. Take one nibble. The thin shell of chocolate snaps between your teeth. The syrup dribbles down your lip. The bright acidity of the citrus bursts across your tongue, balanced with the dark, bitter richness of the chocolate. When you’re done, the sweet orange flavor lingers for a long, long time.

Eating one makes me feel, just for a moment, like a sybarite. Let Pythagoras keep his hypotenuse. I’d take a box of these any day.