What exactly is soy sauce?

Soy sauce is a salty, umami liquid made from fermented soybeans. At a minimum, it is made with soybeans, salt, and fermented with a mold—typically Aspergillus oryzae—known in Japanese as koji.

In the 20th century the production of soy sauce was modernized. Today most soy sauce is made in giant batches at automated factories. Instead of whole soybeans, it is often made with acid-hydrolyzed soy protein—a processed, ground up soybean product. (This is what’s in the plastic packets of soy sauce handed out at many restaurants. It’s also what’s in a bottle of “liquid aminos.”) The modernizations produce soy sauce much more cheaply and quickly, reducing the time needed to ferment the sauce from years to months or even days. It also strips away the subtleties and depth of flavor that distinguish great traditional soy sauce.

What distinguishes traditional Japanese soy sauces from others?

In addition to the standard soybeans, salt, and koji, Japanese soy sauce—called shoyu in Japan—is typically also made with wheat and water. The wheat adds a subtle sweetness to the sauce, and helps to kickstart the fermentation.

Shoyu generally doesn’t contain other flavorings—or if it does, it’s called by another name, like ponzu, a soy sauce with citrus. Soy sauces from other countries often contain a whole range of additional ingredients, from mushrooms to fish to palm sugar to licorice to pineapple.

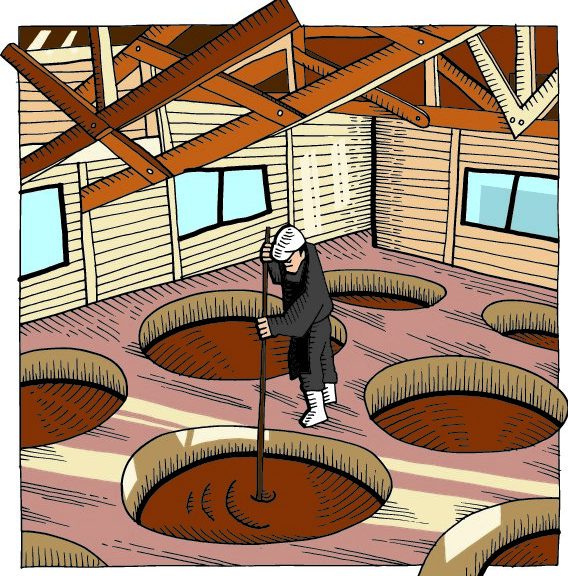

Traditionally, Japanese soy sauce has been fermented in enormous cedar barrels called kioke, each around five feet across and eight feet deep. These barrels hold batch after batch of soy sauce and are often in use for decades. Rather than imparting a woody flavor, they help propagate microbes from one batch of soy sauce to the next, much like how the pine boards in a cheese aging room contribute to the flavor of the cheeses. Today, only 26 soy sauce makers in Japan still use kioke; 99% of soy sauce is aged in humongous steel or concrete tanks.

How is Japanese soy sauce made?

First, steamed soybeans and crushed wheat are inoculated with koji. The koji provides much of the flavor for the finished sauce, just as cultures do for cheese. After allowing the koji to bloom for a few days, the soybeans and wheat are transferred to kioke or tanks and mixed with salt water brine. The mixture ferments for months or years, getting stirred frequently to keep the aerobic microbes active. After the fermentation is complete, the wet soybean paste is slowly pressed, squeezing out the soy sauce over hours or days. Then it’s bottled and ready to sell.

There are five main types of Japanese soy sauce.

1. Shiro — white soy sauce

How shiro is unique: White soy sauce is a pale, straw-yellow color. When soybeans oxidize they become dark, so to make white soy sauce you use mostly wheat and only a little soy.

How it tastes: More delicate in flavor than other soy sauces, it has a subtle sweetness to balance the salty notes.

How it’s used: Traditionally, shiro is used for dishes where you want to add the oomph of soy sauce but you don’t want the color of regular soy sauce to darken the food, like in a Japanese egg custard. Its delicate flavor makes it a good choice for lighter dishes like sashimi. Less traditionally, it’s great for adding a subtle umami kick to everything from broths to tacos to vinaigrettes.

What makes this shiro special: To make the palest shiro they could, third-generation company Nitto Jozo skips the soybeans all together and uses 100% wheat. Since it doesn’t contain soy, Japanese regulation dictates that it can’t be called “shoyu” so instead it bears the name “tamari.”

2. Usukuchi — light soy sauce

How usukuchi is unique: The second most common soy sauce in Japan, usukuchi is made with around 40% wheat, giving it a golden, caramel color.

How it tastes: Japanese light soy sauce is not light in flavor or sodium. It’s the saltiest tasting shoyu by far.

How it’s used: Best used as a seasoning while cooking, like salt. It’s great in broths, stews, and braises.

What makes this usukuchi special: From Suehiro, a company that’s been making soy sauce since 1879, this usukuchi packs a powerfully salty punch. It’s particularly good in broths—especially for ramen or soba noodles.

3. Koikuchi — dark soy sauce

How koikuchi is unique: About 80% of the soy sauce used in Japan is koikuchi. This is the sauce you’ll find on tables at restaurants and in nearly every home. It contains about 15% wheat, making for a very dark color.

How it tastes: Salty, savory, umami, a bit of a fruity sweetness.

How it’s used: The classic soy sauce used for dipping sushi or gyoza dumplings. Great in stir fries, marinades, and sauces. If a Japanese recipe calls for soy sauce without any extra detail, it almost certainly means koikuchi. If a Chinese recipe calls for light soy sauce, koikuchi is a good substitute.

What makes this koikuchi special: From Yugeta, a fourth-generation company, it’s aged for about a year in kioke. It has a subtle wine-y, fruity sweetness that helps balance the salt.

4. Saishikomi — double brewed soy sauce

How saishikomi is unique: To make saishikomi, first you brew a normal batch of soy sauce. Then you take new soybeans, wheat, and koji, and you make a new batch of soy sauce—but for the liquid, instead of water you use the first batch of soy sauce.

How it tastes: The extra aging gives saishikomi a thicker texture and a cleaner, rounder, less salty flavor.

How it’s used: Excellent for dipping sashimi and for more luxurious finishing touches. It can also be thinned out with equal parts saishikomi and water for use in sauces and cooking.

What makes this saishikomi special: From Suehiro, a firm that’s been making soy sauce since 1879. It’s great for sprinkling on richer dishes at the end of cooking.

5. Tamari

How tamari is unique: The process to make miso, a Japanese fermented soybean paste, also creates tamari. Thicker than regular soy sauce, it has great depth of flavor. In the US, many folks think of tamari as gluten free soy sauce. While tamari is generally made with less wheat than other soy sauces, it is not necessarily wheat free.

How it tastes: Complex, very salty, with an umami note like fish sauce or nori. It has a long-lasting finish with a fruity quality that reminds me of raisin.

How it’s used: Try it as a dipping sauce, or brush it on roasted meats, fish, or potatoes.

What makes this tamari special: From eleventh-generation firm Ito Shoten, where they’ve been making miso for more than 200 years. Made with only soybeans, salt, koji, and water, each batch ages for three years in cedar barrels that have been in use for over 160 years.

How does Japanese soy sauce compare to Chinese soy sauce?

While Japanese soy sauces are neatly categorized, Chinese soy sauce has many more variations, and is called by many different names in different dialects across the country. In the US, many of the earliest Chinese immigrants came from the province of Guangdong (formerly called Canton), so what we think of as “Chinese soy sauce” typically stems from Cantonese traditions. There, the common soy sauces are light and dark. If a Chinese-American recipe does not specify which soy sauce to use, light Chinese soy sauce is the standard.

Chinese light and dark soy sauces are not equivalent to Japanese light and dark sauces. If a Chinese recipe calls for light soy sauce, Japanese dark soy sauce is a good substitute. Chinese dark soy sauce is generally thicker and sweeter due to the addition of sugar or molasses. There isn’t a good Japanese equivalent.

How should soy sauce be stored?

Before a bottle is opened, it can be kept at room temperature. Once opened, soy sauce is best stored in the refrigerator and used within 6–12 months. It won’t spoil if you keep it longer or at room temperature, but over time the nuances that make it special will fade.